I. Golden age of Poradnik (1901–1912)

1. About the publication

The foundation of the first Polish popular journal dedicated to language was facilitated by the cultural and scientific atmosphere of Galicia*. The freedoms gained by Poles in the territory of this partition provided for the teaching of Polish and in Polish. In 1869, the Polish language was restored in offices (with the exception of the army and postal service). The process of Russification intensified in the territory of the Russian Partition, while that of Germanisation – in the area covered by the German Partition. The Polish language was either absent, mainly from offices, the army and modern industry, or was strongly influenced by German and Russian. There was no Polish specialist vocabulary in the official language and the press was full of lexical Germanisms and Russicisms, as well as phraseological and syntactic calques*. As the national consciousness increased, the sense of responsibility for the language grew, accompanied by a considerable demand for prescriptive solutions. The gap was filled with publications dedicated to proper language use* and language-related columns in the press*, but there was still no specialist journal in which issues related to proper language use would be raised to safeguard the culture of the mother tongue. This is how the need to publish Poradnik was substantiated by Jan Rozwadowski:

[…] firstly, because attempts to enrich the language are often made by unauthorised people, who do so like apprentices - secondly, because the Polish language has been particularly strongly influenced by foreign languages for over one hundred years, and, what is more, it is not developing in a free and uniform manner [...].

The protection of Polish from being split into three languages must focus first and foremost on counteracting the negligence spreading in the daily press.

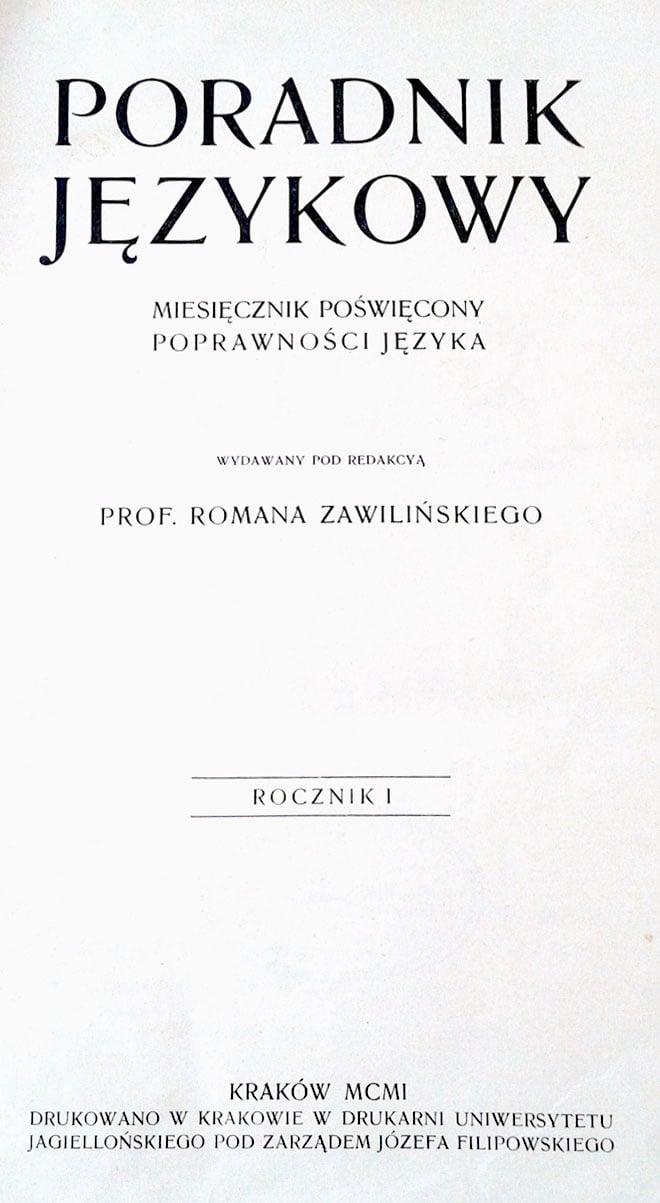

The journal was founded on the initiative of Roman Zawiliński, a teacher from Cracow, who was its publisher and responsible editor until 1931. The editorial office was located first in Cracow, at 22 Karmelicka street. On 1 October 1902, it was moved to Tarnów, and then, on 4 November 1908, it was relocated back to Cracow to 3 A. Grabowskiego street, and at the end of 1912 – 2 Karmelicka street. As the editor stayed in various locations for health reasons, different correspondence addresses were also indicated: Witów (15 June – 30 August 1902, 1902, Issue 6/7, the cover), Krościenko nad Dunajcem (July–August, 1912, Issue 6, p. 81).

The first issue of the new journal on the publishing market was released at the beginning of 1901. This was a monthly with the volume of one author’s sheet. Combined issues* were usually twice that long. Continuous pagination of issues was applied in the annual bound volume. 10 issues were released annually, but in 1906 – 12 by exception*. The periodical was not published in August and September. The total number of 124 issues were released in the period 1901–1912. The subtitle of the journal, i.e. “Monthly dedicated to proper language use” (“Miesięcznik poświęcony poprawności języka”) was changed twice: in 1907 (“Monthly dedicated to proper use of the Polish language” (“Miesięcznik poświęcony poprawności języka polskiego”)) and in 1911 (“Monthly dedicated to issues related to the Polish language” (“Miesięcznik poświęcony sprawom języka polskiego”))*.

Delays in publishing the journal were minor. The editor justified them with personal reasons: an illness (1910, Issue 10, p. 150), moving from Cracow to Tarnów, as well as substantive considerations, waiting for the final arrangements to be made at Mikołaj Rej Convention (Zjazd Rejowski) as regards spelling rules (1905, Issue 10, the cover). Subscribers in Congress Poland received the journal with a delay of 8–10 days, or even more, as the publication crossed the border “through a regular bookselling channel, and was subject to customs duties and censorship” (1911, Issue 1, p. 2; 1910, Issue 10, p. 150).

In annual bound volumes V–X (1905–1910), tables of contents were published at the end of the issues, before the imprints, while in the periods 1901–1904 and 1911–1912, they were provided on covers of the issues, whereby in annual bound volumes I–IV, tables of contents were followed by lists of words explained in a given issue*. The table of contents of a given annual bound volume was published on its cover, while the annual list of the words tackled throughout the annual bound volume was included in the last issue.

The header published on the first page of an issue would always include: the title, year and/or number of the annual bound volume, issue no. (1911–1912) and month (1902–1903). The issues published in 1901 and 1905–1910 provided, besides these details*, the address of the editorial office, information about the release cycle, advance payment terms and main dispatch centres of Poradnik. In annual bound volume IV (1904), the header was replaced with a running head (the title, annual bound volume IV, issue, page); month and the information about the editorial board, advance payment terms and dispatch centres were specified on the cover of the issue. The subtitle of the periodical was provided on the title page of the annual bound volume. The imprint included a copyright disclaimer which read: “Reprinting the following contents either in whole or in part shall be permitted only upon consultation with the editorial board”, replaced in 1904 (beginning with issue 3) with: “[...] permitted only if the source of the original publication is acknowledged”, which was followed by the name of the publisher and the responsible editor, as well as the name of the printing house. The journal was printed by the Jagiellonian University printing house. Printing one issue took approx. 2 weeks (more or less from the 15th day of a month to the 1st–2nd day of the following one) (1901, Issue 2, p. 32). In subsequent issues, the table of contents was followed by the date when the printing process was completed (e.g. the printing of Issue 1 in 1908 was completed on 8 January, while in 1912 – on 3 January).

Advance payments for the journal were collected by bookshops. The main dispatch centres were located in Cracow and Warsaw, and in Poznań for a short time. Considerable interest in the journal prompted its editor to reprint (the 2nd edition of) the annual bound volume of 1901. The amount of the advance payments remained unchanged throughout that period. At a point, advance payments began to be insufficient to cover the cost of publication. Most subscribers made them also at a later date (1906, Issue 4, p. 57). The situation was dramatic already in 1906: “We have faced a dilemma: »to be or not to be«, perhaps we should suspend the publication for some time, until the relationships become stable […]” (1906, Issue 9/10, p. 152). The editor sought to raise additional funds by selling old annual bound volumes, offering subscribers discounted prices for them: “Being unable to offer our dear Subscribers any bonus (neither a car nor gold watches [...]) we have decided to offer you what we have” (1910, Issue 1, p. 16). The readers and friends of Poradnik were repeatedly called to attract “as many subscribers as possible” (1902, Issue 1, the cover), “at least one” (1906, Issue 12, p. 180). Despite the appeals, the number of subscribers did not increase. There were 300 of them in Cracow and Galicia. The majority of subscribers, i.e. 400, lived in Congress Poland, and a small number of them in the Poznań region (Prospectus for 1911).

2. Policy statement

In the policy statement entitled “Nasz cel” (“Our objective”), Zawiliński wrote:

Politics has its numerous papers [...], various professions have their dedicated journals – only language, a tool used by everyone, which everyone needs but not everyone appreciates enough, a tool which is sometimes abused and downtrodden, and which – not being allowed to speak – cannot even complain.

This humble monthly offered to our Readers is to compensate for this gap, which is experienced more and more profoundly. It is not supposed to be a court which delivers severe judgments (as no one has authorised it to do so). Nor does it wish to be a pedantic mentor who proclaims rules and principles developed by himself; its position is clearly expressed in its title – it wishes to be a guide. On the one hand, it will therefore explain linguistic phenomena in the most accessible way, reminding rules and conventions, clarify doubts and uncertainties as regards proper language use in order to correct errors. On the other hand, through recording new phenomena in a meticulous manner, it will be a chronicle of what is happening in the life and development of the Polish language. The first part – a practical one – will seek to provide advice on proper language use, whereas the other one will constitute a collection of a material for historians of the Polish language and linguists.

Zawiliński wanted his publication to serve two important functions: a practical one, which focused on providing advice on proper language use, indicating errors, explaining them, familiarising readers with the principles of proper language use, and a documentation one, which involved recording the linguistic phenomena of those days. The most frequently recurring matters as regards proper language use, which were raised either in papers or while discussing specific forms, concerned: Germanisms and Russicisms in various areas of the Polish language use, professional titles and those used with respect to women, surnames of wives and daughters, pronunciation, spelling and inflection of foreign proper names, language used in business and official letters, as well as professional terminology. Poradnik – as Zawiliński wrote – not only provided advice to readers but also “learnt from others” (1901, Issue 7, p. 109).

Texts published in annual bound volume I (1901) were preceded with the following motto:

Pole, unaware of the treasure you have, spare a thought and listen to advice attentively, and not only will you find enough Polish words to use, but you will even need to choose from their multitude.

After one year of publication of the journal, new sections were declared to be introduced, and so were papers “on general issues written by the most distinguished Polish linguists.” It was also promised that more attention would be paid to “errors in the works by popular writers rather than those in dailies” (1901, Issue 10, p. 146).

Policy issues were raised again at the end of 1903. Leaving the policy outlined in 1901 unchanged, the editorial board declared:

We will seeks to (1) provide more exhaustive replies to questions, (2) revive “Divagations” (“Roztrząsania”), (3) make “Gleanings” (“Pokłosie”) more complete by emphasising not only errors, but also new, yet charming, words and expressions used by authors, (4) provide succinct reports on the latest scientific advances in Polish linguistics, and finally (5) address questions about Polish spelling which explore the essence of the language thoroughly. We will also attempt at a linguistic revision of textbooks as we prepare the relevant material. [...] our hope is that as the journal improves, the number of its Readers will increase and our work will bring a more substantial benefit.

When confronting this declaration with the contents of the journal in 1901–1903, it is worth noticing three new elements, namely the idea to disseminate achievements in the area of Polish linguistics, orthographic issues to be addressed, and the intention to evaluate textbooks from the linguistic viewpoint.

The series of texts devoted to orthography was opened with Zawiliński’s text on the differences between graphics and orthography (1904, Issue 3, pp. 33–35), while an overview of the general orthographic rules was prepared by K. Nitsch (1905, Issue 3, pp. 33–38). Poradnik joined the nationwide discussion on orthography by presenting Brückner’s ideas regarding orthography, the arrangements made by the orthography section of the Mikołaj Rej Convention and Kryński’s spelling. Earlier, issues related to orthography were considered less important:

We have resolved not to start a fruitless struggle about matters of little significance, such as orthography or word division (as these issues are based on arrangements and agreements reached by those who write, and have nothing to do with the development and proper use of language). We are attempting at explaining linguistic phenomena without touching upon spelling, which has no influence on language development.

As regards textbooks, this issue was raised again in A.P.’s letter to the editorial board entitled “Gdzie leży źródło złego” (“Where the source of evil is”) (1907, Issue 8, pp. 105–106) and in the editorial board’s text concluding the year 1907 (1907, Issue 10, p. 137). Linguistic revision concerned textbooks intended for the teaching of reading and arithmetic in community schools in Galicia (1908, Issues No. 1, 3, 4).

Poradnik followed the spelling rules defined by the Academy of Learning (Akademia Umiejętności) (1891), adopted by the Galician School Council (1901, Issue 2, p. 17, Issue 10, p. 146). As requested by A. Brückner and K. Nitsch, the spelling they used in their papers was preserved in the publication.

The achievements of Polish linguistics were presented in Poradnik by: Stanisław Dobrzycki (“Zdobycze językoznawstwa polskiego” (“Achievements of Polish linguistics”), 1904, Issues No. 2–3, 6/7) and Kazimierz Nitsch (“Z badań nad językiem polskim” (“From research on the Polish language”), 1907, Issue 1 – 1910, Issue 8). The former separated contents intended for linguists from those of interest to all readers of Poradnik, he presented research outcomes without exploring “the »mechanics« of science. It [the overview of works – W.D.Z.] is supposed to be only a »conductor« foremost between the mysterious Areopagus of scholars and readers of Poradnik” (1904, Issue 4, p. 29). Unlike Dobrzycki, Nitsch explained the essence of linguistic phenomena stating that “ready-made results only increase – the often excessive – loose and unproductive erudition, at the same time only scarcely contributing to the true development of the mind, and certainly to the understanding of the essence of linguistic phenomena, which is probably of the greatest importance here” (1907, Issue 1, p. 8).

A new initiative was conceived, under which readers were called to collect geographical names on which a Polish onomasticon was to be based in the future. The initiative was not launched, however, until 1920 (Issue 15), when Zawiliński revived this concept. Readers were also given tips: what should be collected and how information should be recorded and gathered*.

Poradnik would participate in celebrating anniversaries of the births of outstanding Polish writers : Rej (1905, Issue 10) and Krasiński (1912, Issue 2). Issue 3 of 1908 was dedicated by the editor of Poradnik to Kazimierz Morawski, a professor at the Jagiellonian University, who taught him in 1878.

The announcement for 1910 pointed to the need to publish papers on general linguistics to “make wide audience familiar with the essence and importance of this science” (1909, Issue 10, p. 156). This does not mean, however, that no texts promoting new directions in linguistics had been published in Poradnik before. In 1906, Mikołaj Rudnicki presented the fundamental theses outlined by Antoine Meillet in Introduction à l’étude comparative des langues indo-européennes (Issues No. 7/8–9/10) in his two papers. In 1903, Zawiliński wrote about the category of grammatical case, referring to Völkerpsychologie by Wilhelm Wundt (Issue 9).

The next step which was to make the journal more scientific involved the introduction of a clear differentiation of contents dedicated to proper language use and lexical enrichment of the Polish language from dissemination of achievements in the field of linguistics. The new formula of the journal was presented in the prospectus for 1911:

I. At the request of numerous subscribers, the practical part will include

1. “Kurs praktyczny gramatyki języka polskiego” (“A practical Polish grammar course”) designed for self-taught individuals, unprepared for school education;

2. in “Divagations”, we will explain all incidental doubts;

3. in “Gleanings”, we will record flaws, primarily in works by eminent writers;

4. in “Treasure box” (“Skarbonka”), we will gather pithy folk words or remind forgotten ones.

II. In the theoretical part, which will be our focus, we will include:

1. general issues related to the science of language;

2. selected information on the history of the Polish language;

3. information on the history of Polish spelling;

4. results of contemporary research on the Polish language (a chronicle of achievements in the area of Polish linguistics).

“A practical Polish grammar course”, the author of which was R. Zawiliński (1911, Issues No. 1–3, 5, 8), focused on syntax.

The authors of the letters sent to the editorial board expressed their support for the activities and initiatives taken by Poradnik. They emphasised that the journal was helpful in school teaching and in the struggle for the purity and proper use of the language in the press. A kind review of the journal was recorded in Książka (The Book) (1902, No. 8), whose author, A. Mahrburg, emphasised the professional nature of the journal and advised that “Poradnik – as a professional publication – should continuously and regularly publish critical reviews of prominent books and magazines, focusing mainly on linguistics issues”, and that “this should be done exhaustively and ex officio” (1902, Issue 10, p. 145). Also Józef Czekalski* defended the journal against the allegation of “incapable editing” made by the Łódź-based Rozwój (Development) (of 21 October 1905).

In mid-1912, the editorial board presented the idea of transforming Poradnik Językowy into Język Polski (The Polish Language) in “Odezwa Redakcji” (“Proclamation”).

The development of linguistic research and its impact on the explanation of a number of phenomena occurring in our mother tongue – both now and in the past – make us focus even more on this new branch of skills, which is starting to bloom charmingly also in our homeland. After twelve years of dealing with the practical aspects of the language, demands are voiced – also by our readers – to disseminate knowledge and present its outcomes in Poradnik. As this is not possible in the existing frames of our monthly, we have decided to extend its volume to 2 author’s sheets beginning in the next year, and also to replace the title with a more general one, namely: JĘZYK POLSKI, and leave Poradnik językowy as its secondary section, where its present character will be preserved, yet given less importance.

Given the indifference of the public (“the interested”)*, the change of its formula seemed also a way to save the publication.

3. Sections of the journal

As declared in the first policy statement, the journal was supposed to be composed of:

(1) general papers providing explanations of important issues;

(2) replies to specific queries and corrections of the identified errors;

(3) a chronicle of new phenomena and neologisms;

(4) reprints of the advertisements, captions, etc. which violated language rules;

(5) a list of foreign words which can be replaced with Polish ones.

In annual bound volume I, the following sections (columns) were identified: I. “Papers” (“Artykuły”), II. “Queries and replies” (“Zapytania i odpowiedzi”), III. “Gleanings from literature and magazines” (“Pokłosie z dzieł i czasopism”), IV. “Stylistic failures” (“Usterki stylistyczne”)*, V. “Neologisms” (“Nowotwory”), VI. “Foreign words” (“Wyrazy obce”), VII. “Discussion” (“Dyskusja”), VIII. “Linguistic drolleries” (“Krotochwile językowe”), and the following items were included at the end (besides numbering): “Editorial board’s letters” (“Korespondencja redakcji”), “Corrigendum to page 60” (“Sprostowanie do str. 60”), “List of words and expressions explained in annual bound volume I” (“Spis wyrazów i zwrotów objaśnionych w I roczniku”).

In annual bound volume II, “Discussion” was replaced with “Divagations” (“Roztrząsania”) (section III). The following sections were added: “Treasure box” (section V) and “New books” (“Nowe książki”) (section VIII). In the subsequent annual bound volume (1903), the “Editorial board’s letters” section was given the same significance as others, and was classified as section X. A new section (VII) was introduced to deal with “Technical vocabulary” (“Słownictwo techniczne”). This section was launched with a series of papers on Polish specialist (professional) terminology: “Z dziedziny żeglarstwa powietrznego” (“In the area of air navigation”) 1909, “Słownictwo zawodowe (farmaceutyczne)” (“Professional (pharmaceutical) vocabulary”) 1912. This task was difficult not only because Polish terminology was only being developed in a multitude of fields, but also due to limited access to professional sources (1911, Issue 1, pp. 1–2). The breakdown into sections was not consistent, certain names of the sections identified in the annual bound volume were the titles of the texts published in the issue (e.g. in annual bound volume IV: “Protest grona Czytelników” (“A protest of a group of Readers”)). The layout of sections in issues varied, even regular sections did not appear in each issue (e.g. there is no “Papers” section in Issue 8 of 1902). The number of sections in the annual bound volumes published in 1901–1912 ranged from VIII to XVI. The issue usually* began with “Papers” (this section was sometimes preceded with the publisher’s note, e.g. “Zaproszenie do przedpłaty” (“Encouragement to make a prepayment”), 1909, Issue 1, p. 1), which was followed by other regular – more or less frequently occurring – columns: “Queries and replies”, “Divagations”, “Gleanings”, “Treasure box”, “Neologisms”, “Foreign words”, “New books”, “Linguistic drolleries.” Although the contents of the individual sections were defined, texts devoted to similar issues or having a similar form were sometimes included in different sections*.

“Papers” concerned general and specific topics approached from the theoretical perspective. The first paper, published in the first issue of 1901, was dedicated to inflection of surnames with the fleeting ‘e’, like in Grudzień or Kociołek, which have been troublesome to Polish language users to this day. That section included usually one or two texts. This number was occasionally increased to three*. The column was supplemented also (in some of the annual bound volumes) with vital texts written by the editorial board, e.g. in annual bound volume I (1901): “Nasz cel” (“Our objective”) (Issue1, pp. 1–2), “Od Redakcji” (“Editor’s Note”) (Issue 2, pp. 17–18), “Po roku” (“A year later”) (Issue 10, pp. 145–146). In 1901–1912, a total of 122 papers were published (1901 – 10, 1902 – 8, 1903 – 12, 1904 – 10, 1905 – 10, 1906 – 9, 1907 – 8, 1908 – 11, 1909 – 8, 1910 –16, 1911 – 10, 1912 – 10).

Due to the limited volume of the issue, the papers had to be short (from 2 to 5/6 pages). They were also published in chunks. “Błędy językowe prasy warszawskiej” (“Linguistic errors found in the Warsaw press”) by Aleksander Łętowski was the longest paper published in a single issue (1912, Issue 4/5, pp. 49–63). The text was endorsed as follows:

We dare not to agree with the Author on numerous issues raised here. We do, however, publish these remarks in their entirety, as the author – being a journalist himself – represents these social spheres and reveals their deficiencies.

Enquiries sent to the editorial board were published and followed by relevant replies in the “Queries and replies” section. The published enquiries concerned specific words (their inflection, pronunciation, morphology, order in the sentence, or meaning). More general issues, such as the adjective-noun order in the sentence, were raised less frequently (1906, Issue 3, p. 41). Readers would also ask about Polish equivalents of foreign words, primarily German ones, but such questions ceased to be replied to at some point, which was justified as follows: “Such issues should be handled in a dictionary rather than in Poradnik; for the sake of space, we will no longer reply to such questions, unless the enquirer proposes a translation himself and asks for its evaluation” (1906, Issue 1, p. 2). Enquiries sent by the 15th of each month were replied to in the issue published next month. Sometimes, however, due to plenty of material to be published or a unique character of the issue, e.g. the one dedicated to Rej (1905, Issue 9, p. 144), they were published in later issues (1902, Issue 8, p. 128). Until 1905, enquiries were arranged by their subject matters (by grammar sections). Afterwards, they were arranged in the order in which they were received by the editorial board. In the annual bound volume of 1901, a total of 281 queries were replied to (the queries were assigned consecutive numbers), in 1902 – 248*, in 1903 – 174, in 1904 – 179, in 1905 – 173. From 1906 on, queries were numbered again. In 1906, 140 queries were published, a year later – 43, in 1908 – 70, in 1909 – 75, in 1910 – 42.

“Divagations” were devised as an explanatory comment on the matters dealt with in the “Queries...” section and as a platform for sharing views on linguistic issues, including the resolutions on proper language use published in Poradnik*. This section would also include responses sent by the authors whose language was evaluated in “Gleanings.” Some of them were quite fierce, e.g. that of Aleksander Brückner (“Pro domo”, 1904, Issues 4–5) in his reaction to the linguistic errors pointed out to him by Ludwik Czarkowski in “Gleanings” (1904, Issues 1–3). Czarkowski was defended then by Zawiliński (1904, Issue 6/7).

Individual contents in this column could be singled out with separate titles and, in some cases, they were numbered. To satisfy the expectations of serious Readers, “in order to change the tone and scope of replies to queries”, beginning with Issue 1 of 1911, replies to enquiries turned into “true divagations on doubtful issues”, the “Queries and replies” column and the “Divagations” section merged into one (1911, Issue 1, p. 1). This approach prevailed also in 1912. In 1911, 40 linguistic issues were raised in this section, while in 1912 – 63.

“Gleanings” discussed linguistic errors, as well as the Russicisms and Germanisms found in the books, newspapers and dailies published at that time. Works written by authors such as Henryk Sienkiewicz, Wacław Gąsiorowski, Andrzej Strug and Stefan Żeromski were analysed. In 1901, errors found in 35 magazines and 15 literary works were subject to evaluation (1901, Issue 10, p. 145). Zawiliński attached great importance to that section: “This section is important, perhaps even more important than the others” (1906, Issue 1, p. 2). He believed that if editorial boards of all magazines “resolved to first and foremost eradicate linguistic failures and errors in all writings, but primarily in their own” and followed the advice given in Poradnik, “then having united our forces, we would accomplish our objective more easily, as collective work would yield greater results in a shorter time than an individual effort”*. He emphasised that:

Theory and practice must go hand in hand, and not separately; writing shorter or longer papers on language purity while violating the most important language rules will not only fail to be beneficial, but it also embarrasses others and reminds of the parable about false prophets from the Bible [...].

In the first annual bound volume, errors were discussed from two angles: by their type (i.e. errors in spelling, pronunciation, inflection, syntax, semantics, Germanisms, Russicisms and Galicisms, as well as stylistic failures), and they were less often recorded in the order in which they occurred in the text (1901, Issue 5, pp. 75–79). In subsequent annual bound volumes, errors were no longer classified in such a detailed way – their certain types (e.g. Russicisms) were discussed instead, or lists of the words and collocations deemed incorrect were compiled (incorrect forms were usually only followed by correct ones).

In “Treasure box”, the editors gathered folk words and neologisms “which in each respect deserve to be included in the language of literature, particularly where a foreign word stands proudly” (1902, Issue 1, p. 14). In order to encourage readers to send words to be included in the treasure box, the editorial board resolved to publish questions and treat replies to them as “the proverbial widow’s mite.” The first question concerned folk names of degrees of kinship (1903, Issue 3, p. 49). A great deal of attention was paid to the precise localisation of folk lexis, “otherwise the most charming expressions lose their value” (1902, Issue 5, p. 80). The “Treasure box” contained, e.g. żywizna (livestock) from the Mława region (1902, Issue 6/7, p. 143) and wołoszka (a word used for the overcoat in the Poznań region) (1903, Issue 9, p. 149), as well as neologisms from Ballada o słoneczniku i inne nowe poezyje by Jan Kasprowicz (1909, Issue 1, pp. 9–11).

The “Foreign words” (“Wyrazy obce”) section provided lists of foreign words and their suggested Polish equivalents. The editors’ intention was “[not] to let this section be overwhelmed by usually misfortunate ideas stemming from an unhealthy desire to Polonise everything” (1906, Issue 4, p. 63). It was clearly emphasised that “we do not believe that all [words] should be eliminated, as the concept expressed by a foreign word cannot be in some cases expressed by one Polish word...” (1902, Issue 4, p. 64).

The “New books” section contained information – sometimes worded very laconically – about interesting and useful books dedicated to linguistics (Polish grammar books, dictionaries, guides, and orthography books) and studies by Polish linguists (Karol Appel and Stanisław Szober 1908, Issue 5, pp. 79–80). More detailed information was presented with respect to linguistic journals: Prace Filologiczne (Philology Papers) and Rocznik Slawistyczny (Slavic Yearbook) as well as the outcomes of the research conducted by Jan Baudouin de Courtenay (1905, Issue 2, pp. 30–32). Due to the scope of its comments on proper language use, Artur Passendorfer’s review of Antoni Krasnowolski’s book entitled Najpospolitsze błędy językowe of 1903 (1904, Issue 2, pp. 29–32) might have as well been placed in the “Gleanings” section.

In 1911, a new section was introduced: “Research findings” (“Wyniki badań”). It presented results of scientific research on the Polish language. “If »new books« are intended for practical use rather than dedicated to research, we will discuss them in the same column as we have done so far” (1911, Issue 1, p. 1).

In 1912, a new column appeared: “Reprints” (“Przedruki”) (as Section VIII)*. Until then, reprinted texts (derived most frequently from journals) had been included in other columns, e.g. “Miscellaneous” (“Rozmaitości”)* or “Papers”*.

“Linguistic drolleries” (published sometimes on the cover of the issue) contained short texts worded in a clumsy way, which had unintended amusing effects. One of them is the following medical certificate:

J..S... shall be exempt from gymnastics classes because, as I informed already a year ago, this activity – for no known reasons – has adverse effects on him and he will be then down with headache.

“Given the abundance of serious material”, this section could be most easily abandoned (1905, Issue 3, p. 48).

4 Collaborators

From the moment of its foundation, the journal was intended by the editor to be a joint project implemented by readers, the editor and language experts (linguists). Zawiliński believed that “sharing ideas” was one of the main functions to be fulfilled by Poradnik. Therefore he was very attentive to opinions of “those who are not professionals, not educated, yet love their mother tongue” (1905, Issue 5, p. 65). He also shared his excessive load of duties with readers: “The editor, burdened with the responsibilities resulting from his profession, cannot read only for the purpose of linguistic evaluation, and does not have enough time to read with this aim in mind; he performs this duty willingly but cannot perform it ex officio” (1902, Issue 10, p. 146). The first policy statement was concluded with a request addressed to language enthusiasts for help (collaboration) in accomplishing the adopted objectives by sending enquiries or excerpts, advertisements and inscriptions containing linguistic errors (1901, Issue 1, p. 2). Zawiliński held the opinion that “the multitude of queries and active participation of people representing various backgrounds and regions in divagations attest to the interest in linguistic issues, reflection while in doubt, simply the beginning of a sense of language, the basis of sound and true correctness... even that would mean something, definitely more, much more, than nothing” (1902, Issue 10, 145).

Among collaborators of Poradnik there were its readers and friends – not only from the territory of the former Republic of Poland (i.e. Galicia, Congress Poland, the Vilnius and Poznań regions), but also those living in Berlin, Yaroslavl on the Volga River and even Cairo. These were, among others, priests (e.g. Ignacy Charszewski, the parish priest from Płock – Trzepowo), engineers (e.g. Mieczysław Geniusz, the director of Water Supply Plant in Port-Saïd), university professors (e.g. Stanisław Ciechanowski, a medical doctor, Jagiellonian University in Cracow; Mieczysław Kowalewski, a zoologist, the Agricultural Academy in Dublany; Kazimierz Twardowski, a philosopher, the University of Lviv; Stanisław Witkowski, a classical philologist, Jagiellonian University in Cracow). Their texts and enquiries were signed – as requested – with their full names, abbreviated surnames or initials. Those without signatures were ignored. Errors found incidentally by various people were published anonymously (1906, Issue 7/8, p. 106, footnote 1).

The editor would refer to opinions presented by the journal’s readers and enthusiasts of the Polish language in matters awakening strong emotions, such as:

1) the attitude to foreign words:

1. What is your view on foreign words in general, and in particular those which come from more modern languages (French, German, Russian, etc.)?

2. Which foreign words (perceived as foreign) should be retained and which should be replaced with Polish ones? (to be listed in general).

2) the spelling of foreign surnames:

How should foreign proper names be spelt? Should they be left in the original foreign form or adapted to Polish pronunciation?

Writers and columnist were sent a questionnaire on the formation of female surnames (of wives and daughters), composed of the following questions:

1. Is it consistent with the nature of the Polish language to give women male surnames such as Marya Schneider, Helena Puppenspiel, Otylia Czerny or even Zofia Dunin?

2. Should the use of suffixes -ówna, -anka be limited to certain surnames only?

3. Would such ossification of surnames not entail invariability of surnames ending with -ski, -cki, e.g. Monika Krowicki, Helena Ślaski?

The questionnaire was distributed among 80 individuals, 16 of whom responded. These were e.g. Oswald Balzer, Wacław Gąsiorowski, Tadeusz Korzon, Ignacy Matuszewski, Eliza Orzeszkowa (1907, Issue 6/7, p. 86).

Readers were asked questions about Poradnik itself: what it should look like, whether it satisfied their expectations, what requests they had (1910, Issue 9, Issue 125; 1909, Issue 10, Issue 156).

The quality of the journal improved and theoretical reflections became deeper when the following persons agreed to become permanent collaborators: in 1904 – A.A. Kryński from Warsaw, Stanisław Dobrzycki from Fribourg (Switzerland) and Artur Passendorfer from Lviv (1903, Issue10, p. 164), in 1907 – Kazimierz Nitsch, Ignacy Stein and Piotr Jaworek*. It was expected that “Prof. Stein will handle enquiries and replies as well as divagations related to them; Prof. Dr. Nitsch will provide account of the achievements in the field of Polish linguistics, whereas Prof. Jaworek will be responsible for evaluating neologisms and spelling issues” (1906, Issue 12, p. 180).

In 1908, Jan Rzewnicki joined the group of Poradnik’s collaborators (1937/38, Issue 4, p. 33) – an engineer and an enthusiast of the Polish language, who greatly contributed to the codification of the Polish electrical engineering terminology.

This list of collaborators is, however, not exhaustive:

We do not name all scholars whose collaboration is an honour for us; we can, however, make an assurance that we are making efforts to attract each and every collaborator in this field.

It should be noted that in the annual bound volume of 1901 (I), the “Papers”* section comprised 9 texts, while only one of them was provided with the name of the author, that is Kazimierz Nitsch. Zawiliński’s name is affixed to 41 papers as their author and one as its co-author. It is very likely that Zawiliński was also the author of papers published anonymously (13 texts, including 6 about Poradnik itself) or signed by the editorial board (1). It can be thus assumed that he wrote about 45% of all the papers in the period 1901–1912. Zawilliński was followed in terms of the number of papers published by: Ignacy Stein (9), Kazimierz Nitsch (7), Piotr Jaworek (5), Jan F. Magiera (5), Jan Czubek (4), Szymon Matusiak (4), Henryk Ułaszyn (3), Jan Bystroń (2), Aleksander Łętowski (Al. Ł.)(2), Artur Passendorfer (A. P.)(2), Mikołaj Rudnicki (2). The following authors wrote one paper each: Karol Appel, Tytus Benni, Adam Braun, Antoni Danysz, Stanisław Dobrzycki, Stefan Kecker, Romuald Koppens, Mieczysław Kowalewski, Mirosław Kryński, Tadeusz Lehr (Spławiński), Jan Łoś, Julian Morelowski, Józef Peszke, Jan Rozwadowski, Lucjan Rydel, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Czesław Świerczewski, Kazimierz Twardowski and, signed with initials: mg. and W. S. As regards co-authors of papers, the following persons were mentioned either in the annual list or in the issue: Walerian Staniszewski and F. Ruszkowski (1), Mieczysław Geniusz and Franciszek Prus (1), Zweigbaum and R. Zawiliński (1).

The editor’s efforts to attract outstanding linguists as collaborators were not always successful. In Issue 1 of January 1912, Zawiliński wrote:

There are linguists who refuse to write anything to Poradnik because this title turns them off and they would consider it an offence (?) to have their papers published in a secondary periodical intended for the general public for the purpose of learning and applying in practice.